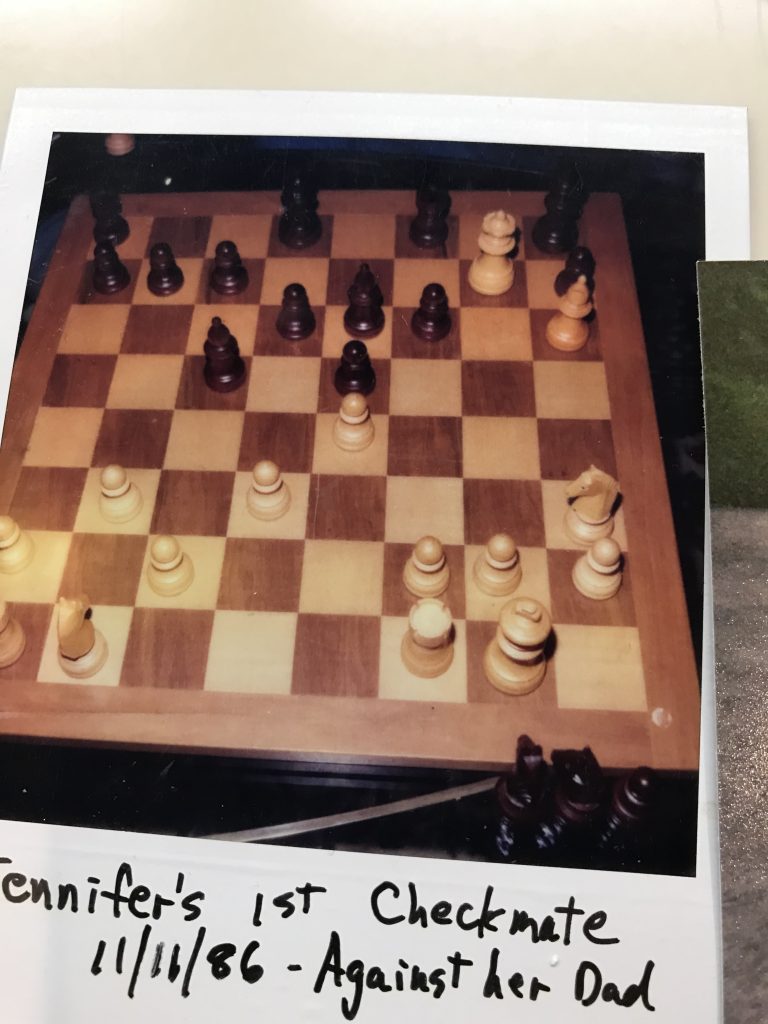

The above image chronicles the last time I played chess with my dad. I was almost 9 the day that I beat him. He snapped a polaroid, bragged about it to others, and never played with me again. Eventually I found other people to play with, one friend who was a boy, and mostly boys in my high school chess club who were seriously tournament-playing with a timer during lunch hours and more interested in having me as an audience member etc. than letting me play. I didn’t really pursue it much after that as my attention turned to other things. What’s funny is that my grandad, my dad’s father, taught my grandma to play. And she beat him the first time she played him. He actually threw chess pieces around the room and never played with her again. She took up Mah Jongg with her friends and won almost every game. In her assisted living home where she went to live after my grandad passed away, they had games of skill and chance, and she won both unapologetically almost every time.

But back to my dad, he was a tricky father to grow up with, and it’s almost funny to look back on some of my times with him now. He would confide in me about his problems with my mother, and tell me when he thought she was being unreasonable with me. My mom liked to describe him as having a touch of Asperger’s and to this day, almost two decades after their divorce, won’t concede that he was also narcissistic.

We did some great things. We went on one scuba vacation when I was 17 or so, and my dad was upset to learn that I used less oxygen than he did. We were dive buddies and at one point under water, he came close to running out of air. He swam up to me, with a panicked look at one point. I suddenly realized with clarity that if he were to run out of air, he wouldn’t think twice about taking mine. We ascended to the surface, but the realization shook me for awhile after that.

As I grew and had opportunities, he wanted to join in them. 8th grade math club – he became a parent club leader because he wanted to do the math problem sets. Though I was supposed to grow up to be a chemist, physicist, or doctor. No other professions were considered valid. Asian Civilization class in high school: he took my books from the class, then took himself to China. He has not yet returned my books. He also took my books from Spanish class, and then had an affair with a woman from Latin America the summer after I graduated college. “Jen, this family is broken. I’m having an affair with a Sandinista from the coffee shop at work who has an AK-47. Should I tell your mom? What should I do?” When I took a sailing class, which I hated, he bought a Laser sail boat, took me out on the mountain lake that could have stiff winds without knowing how to sail himself, but wouldn’t let me steer. We capsized three times. A storm came up, and someone in a motorboat came out to rescue us, which was humiliating for my dad. I was hypothermic by the time we were rescued and had to have a rescue blanket.

One night, after I’d found my girlfriend in Portland, I talked on the phone with him after he’d had something to drink. “I have to go eat dinner” I said. “Don’t eat the pussy,” he said smarmily. “It’s really gross.” He hates cats.

Every weekend when I was in high school, we would go together as a family to the mountains on my dad’s prerogative. There was no way to opt out. We had to be ready to go by the time he got home from work on Friday night or he would throw a fit. I missed all the high school parties, never even tried weed till I was halfway through college. Because I was coming to terms with my lesbianism, I didn’t totally mind missing all the high school social events, but I think I could have used more of a social life. At that point nobody was out in high school. By the time my sister reached that age they were more relaxed, letting her bring friends up or spend the weekend with friends instead. Perhaps they worried that I was gay because I hadn’t been allowed to have more of a social life and wanted to make sure my sister wasn’t so locked down. Summer camp was incredibly transformative because it allowed me to have a time and place to develop friendships and forge a connection to the mountains on my own terms, without my dad controlling and mediating the experience, or the forced march of the hikes he chose. When I would challenge him, my mom would implore me to stop being difficult and stubborn.

When I was a senior in college and came back for vacations, I realized that I’d emotionally outgrown both of my parents, which is a bit of a shattering realization to have. They told me they thought that what I called empowerment indicated only that I’d been brainwashed at my women’s college. My mom still hopes that I’ll realize I’m straight. But the transformation of that last magical last college year, when everything seemed to coalesce and integrate and I found the start of an academic stride and belief in my abilities stayed with me to a point as a new way forward through life, even if it has at times come into question, or something I see now as more of an idealized vision than of something which can correspond with external reality in all ways I’d hoped, and the double-edged fortune of being able to grow into such a supportive environment – so difficult at times to re-create or to validate in retrospect.

My dad and I still occasionally try to have a relationship, but then it all flies south. It usually starts with my dad showing up with a grand financial gesture and an idealized vision. A trip to Europe, where I will do all the interpreting. A bike trip to ride the French Alps. A ski day where he can be proud that I ski like he does. When I turned 40, it was a mountain bike trip – though it had to be one he chose. We went to Moab for a 4-day bike of the White Rim. I was a strong rider and could stay at the front of our group. My dad, who had become deeply interested in geology (a room in his basement is now filled with rocks and he has three different geology microscopes), took his time to look at rocks and stayed close to the back of the group. On the penultimate day of this 4-day ride, he exploded. “You little bitch,” he confronted me on the rim of the canyon. “Can’t you see my hip hurts? I’m at the back of the group. Selfish ingrate. You haven’t biked with me enough. This is our last trip together. I don’t ever want to see you again. And you’ve gained weight. You’re my biggest disappointment.” I calmly told him that I believed that he had been looking at rocks and had been happy taking his time, and that everyone is only competing against him or herself. “Shut up.” he said, suddenly afraid that the other group members would hear. We ended the trip, and he didn’t talk to me at all during the whole 6-hour car ride back to Colorado. “Have a nice life.” he said as he dropped me at my mom’s house.

Over time I’ve come to understand now that he has very limited emotional bandwidth and not much room to operate outside of picking up his marbles and leaving the playing field when he doesn’t win, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t hurt every time. On the other hand, my dad never had many others standing up to him or stayed in situations where he was confronted. I was someone he couldn’t escape who did stand up to him, and one time he told me that he thinks I’m one of the strongest people he knows. But there was always a price for it. I’m definitely the black sheep of my family.

I think that my experiences with my dad compelled me to try to find a different way, also set me up to understand that sometimes success comes with hidden costs and agendas, that sometimes gifts are for the giver, that some battles are more worth fighting that others.

What threw me was thinking I had found something different in my ideals about academia, which felt oddly familiar though I couldn’t explain why to myself at first, only to realize that no, others do not always support or welcome or honor one’s success, and actually this sort of blindsided me because I thought I’d had better judgment than to let myself in for more of that sort of pain. At first I didn’t understand why some of the older grad students seemed to make a point to keep their heads down, to underperform. I thought it was sloth, or maintaining a status quo. I didn’t fully appreciate that it was a sort of compromise for survival, and that, being idealistic, I was not somebody who could live well or non-self-destructively with making the sorts of compromises one often has to if one wants to survive where there are hard edges of people at play. The shame, fear and anger of tolerating unfairness or abuse could eat me alive. Which sort of leaves one floating in a no-woman’s land of not knowing anymore what is safe or who to trust, and unwilling to throw more effort at it.

It’s always been easy to try not to be narcissistic or repeat those patterns, but it’s been hard to unchain that from also not having success. Like if one has success without power one gets squashed, but success with power makes people narcissistic through some mysterious alchemical process. Which I know is false, and certainly there are enough examples around of successful people who don’t need to take others down, but somehow it’s still hard to believe.